Fifteen years after the centenary Monotype Recorder (published in time for the ATYpI 1997 conference in Reading) the title was revived, this time to celebrate the four-decade long career of Robin Nicholas. There were copies available at the shop of the Pencil to Pixel exhibition, but they have not yet circulated worldwide. This text was my contribution.

Forty years is a long time, by any measure. In typography and typeface design, the last forty years are aeons, encompassing tectonic shifts in the industry. From stable, verdant summers to tumultuous storms and heavy winters, to hesitant then blooming springs, the type industry has seen more change and upheaval in the last few decades than in its previous centuries combined. We know of large companies that ceased to exist, others that transformed into very different entities, and of new ones – small and sometimes getting larger – that are growing into a new environment. And yet, the core principles of typeface design somehow persist, mutate, adapt, and survive the changes.

The company that Robin Nicholas joined is probably the most interesting, and certainly the most persistent survivor. At the time of his joining Monotype as a young draftsman, the industrial behemoth smelting heavy but precise machinery for dispatch to a global market must have seemed like a mountain of granite, immovable through the scale of its commerce and the confidence of its technology. Indeed, expanding his letter-making skills from two to three dimensions in his first years pointed to techniques handed down to apprentices for centuries before his time. And yet, before long, accelerating changes started introducing new ideas in typemaking. The swishes and squirts of pumps gave way to the clicks of flashing lights, and soon after just the hums of cooling fans and the low buzz of electronic devices. The process of making letters lost a dimension: from drawings to ink, the miniscule ridges and valleys of carefully cast metal gave their place to letters cut out of light (more changes were yet to come). New collaborators brought very different skillsets into typemaking, to be replaced in their turn by a dispersed, localised, and by comparison chaotic community. This story is often told, and well-known by all typeface designers and typographers, and we do not need to dwell on the details. Yet, it is only marginally a story of typeface design: it is one of typesetting, of documents in front of readers’ eyes. These documents responded to the seismic industrial upheaval by filtering typography through the new technologies: a great part of their conventions survived, at the level of the letter, the word, and the paragraph. Many more changed, most visibly in layout, and document structure. Primarily, and from our point of view, the technological shifts have been a story of ideas about typefaces surviving across technologies, like a vessel floating from a river to an estuary to an open sea.

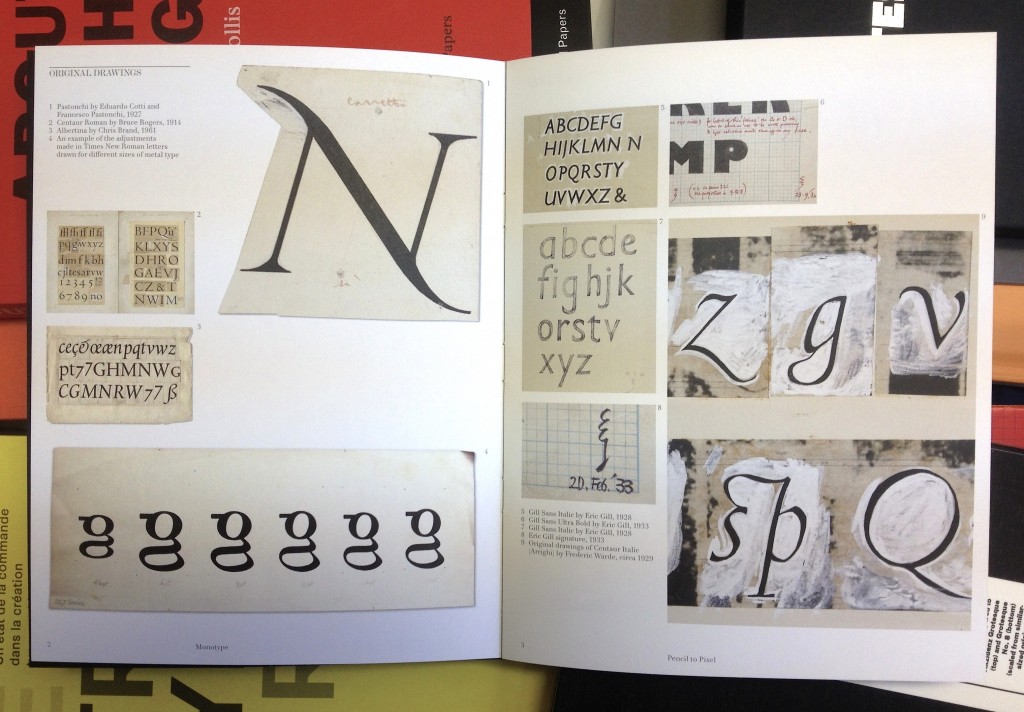

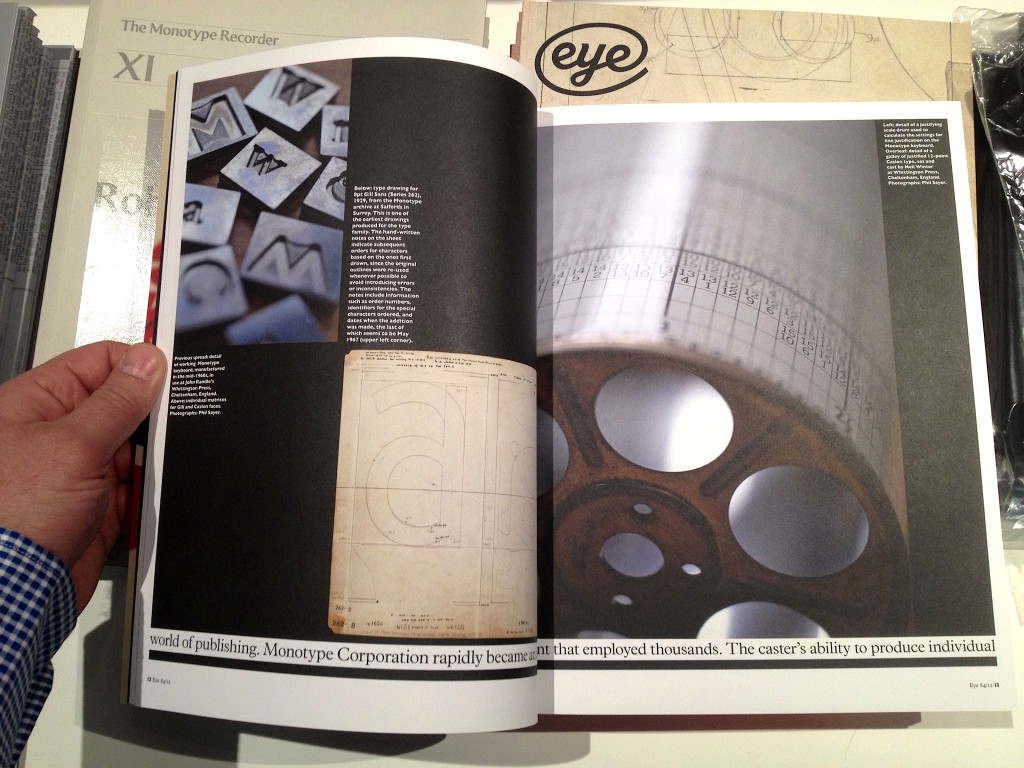

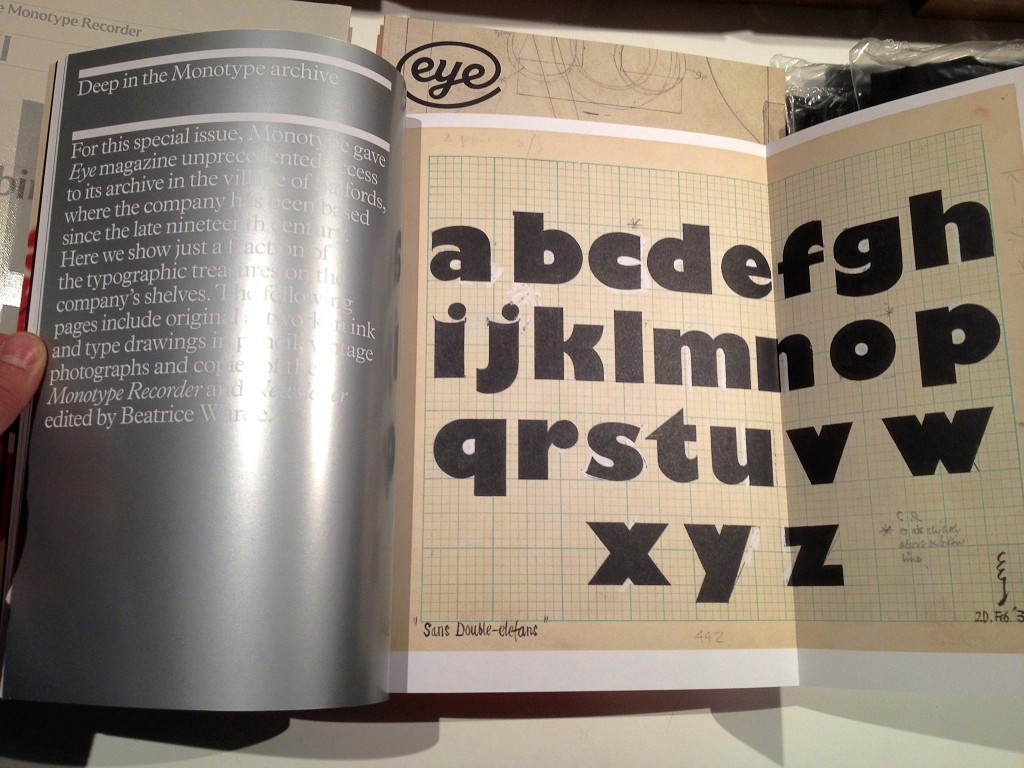

Robin’s career has almost entirely coincided with these fundamental transitions in the way typeface designers capture their intentions, and then encode them for production. Precise paper drawings for the letter shapes, specific for each range of sizes, survived across technologies more than people would expect. The delicate pencil outlines captured details in ways that it would take decades for screens to match, even if they gradually lost a lot of the formality of their earlier years (for a brief period of time making beautiful rubylith transparencies the apogee of flat encoding: in many ways, the most pristine form that letters have ever been stored). Downstream of the sheets of paper, however, the story is very different. Once drawings could be stored on a computer, it is not just the direct relationship to the rendered sizes that is missing (away from a punchcutter’s desk, this was never really present).

Letter shapes stored as digital constructs abstracts them from a rendered reality, and makes the drawn letters only a beginning in a process of shape manipulation on a scale that twisting lenses or rheostats could not begin to hint at.

These transitions placed unique challenges for a designer whose career spanned such changes. Superficially, the designer would participate in changing the ways of doing things: new units of measurement, new equipment down the line, new production processes. More visibly, a new class of professionals joined the companies, with a language for describing the making and rendering of letters that would seem alien only a couple of decades in the past. But fundamentally, the changes in typesetting technologies forced a reflection on the key skills of a typeface designer. At the beginning of Robin’s career it would be easy to assume that the typeface designer was inseparable from the making of pencil renderings on paper. The only distinction one could make would be between the degrees of seniority (a draftsman, a designer, the Head of the Drawing Office), to which different levels of privilege for making changes would be assigned. But from when the locus of the designer’s decisions became fluid and transferable across type-making technologies, the contribution of the designer needed to be more carefully articulated. A – not at all rhetorical – ‘what is it that I am really adding to this process?’ has been central to deliberations on typeface design from the mid-sixties onwards (neatly overlapping with Robin’s career). The loss of directness makes this a critical reflection: letters are not anymore perceptible in any approximation of their true form as they travel though each process, but only witnessed indirectly though human-friendly compromises – as every digital technology demands.

Faced with this question, the typeface designer will invariably return to the fundamentals that survive the technological shifts: the designer’s craft involves decisions about typographic patterns and shape details at a level abstracted from the encoding of the shapes, and the mechanisms of rendering. In other words, the designer imagines an idealised visual and intellectual experience by the reader that is derived from a particular typeface, and will strive to make this a reality through – and around – the technology at hand. Robin’s work offers some particularly good examples of this three-way dialogue between the designer, the ideal model of a typeface, and the technology used to capture it, none more so than the revivals of historical types. Is a true Bell, a Centaur, a Fournier, a Janson, a Van Dijk, a Walbaum one closest to the imprint of metal types in the sources – and, of those types, which? In these we see a masterly distillation of a whole range of possible appearances into a definitive set of shapes that have defined typographic reference points. Such digital classics defined not only mainstream textures for typographers and readers, but also an indirect basis for the digital explorations of the 1990s, which found a voice by negating the refreshed historical models. And the approach to the chameleon that is Dante, and the revisitation of Bembo in Bembo Book, show an exceptionally delicate adaptation of style to the digital medium. (Although we must admit that not even Robin’s skills can help the historical accident that is Pastonchi…)

Next to revivals, the other big challenge for typeface designers is a very tight brief for a text-intensive design, of which none more so than newspaper typefaces. These must meet extremely high functional parameters, in tight spaces and with requirements of economy and stylistic discretion that make the achievement of a distinguishing identity the typographic equivalent of hitting a bullseye blindfolded. Yet, the longevity of Nimrod, whose combination of gently swelling terminals and deep arches on the x-height, with an light, strong baseline set a much imitated pattern: directly in new designs even thirty years later, but also in hints that when applied to Scotch Romans updated a style that is one of the dominant styles for text typography to this day. The same pedigree of absolute control of a dense texture (and a familiar clarity in the horizontal alignments) can be seen in the more recent Ysobel, which updates the style with a more self-indulgent italic. Ysobel’s italic is not only a response to rendering improvements in news presses since Nimrod, but also an endorsement of the contemporary rediscovery of the potential of italics in text typefaces, and the gradual abandonment of historical models for the secondary styles.

Whereas revivals and text-intensive typefaces are most illuminating of the designer’s skill, Robin’s work with typefaces for branding and OEMs testify to a side of his work that is not possible to list in a type specimen. For those of us that have had the pleasure of working with him, Robin exemplified the quintessential collaborator: he combines mastery with humility, and confidence with a sincere willingness to discuss a design, and share his expertise. At the heart of his approach lie a deep respect for his fellow designers, and constant striving for learning and, in turn, contributing to the discipline. (I remember fondly sitting with Robin over a stack of printouts with an OEM Greek typeface, our discussion taking us from the shapes in front of us to a pile of books and specimens that would help us answer why a particular treatment of a bowl is true to the style and appropriate to the brief, rather than just formally pleasing.)

This combination of openness and respect for the discipline of typeface design points to two key aspects of Robin’s work, not directly related with any shapes he made. First, his nurturing of several designers that worked under his supervision at Monotype. And secondly, his dedicated efforts to support education in typeface design, not least through his involvement with the masters programme at Reading. As an External Examiner, Robin has directly influenced the direction of education in typeface design; as an advocate for the concrete support of promising applicants he has helped change the lives of a small number of people in very real terms.

I am leaving for last an area of Robin’s contribution that perhaps few people outside the company know much about, but has been paramount in supporting an extremely important trend, as well as foreground the unique nature of Monotype. Through his engaged stewardship of the Monotype Archive in Salfords, Robin has enabled numerous researchers in their work in Latin and non-Latin scripts. This has had a critically beneficial effect in the typefaces designed, and – even more importantly – in the documentation that is available to the next generation of researchers and designers. It is no understatement to say that Robin’s support for the integration of archival research into our postgraduate projects is benefiting in fundamental ways the skills of the younger generation of typeface designers from Reading, and, though them, the appreciation of a research-informed approach in the wider typeface design community. (We should note that Robin is far from alone within Monotype in his active support of education and research: the company is highly sensitive to the unique legacy it holds, the real value for contemporary design of the knowledge embedded in its archives, and the benefits of supporting students at a range of levels.) It would be remiss of me to omit Robin’s involvement with the first Knowledge Transfer project between Monotype and the University of Reading. The project, which demonstrated in concrete terms the value of the Archive in Salfords for the development of new typefaces for the Indian market, captured a key moment in the globalisation of typeface design and the shift towards screen-based texts, and, specifically, mobile devices. The project also enabled a marketing narrative of differentiation based on concrete and deep expertise spanning decades; arguably Monotype is the only active company able to make that claim with regard to the support of non-Latin scripts.

I hope that I have done justice, in the limited space here, to Robin’s long and diverse career. I have attempted to paint a picture of a consummate professional, adaptable to the conditions of his industry, reflective about his practice and the fundamentals of his discipline; an enlightened collaborator, keen to share expertise and support the growth of a younger generation of professionals; and – crucially – a Type Director with a clear vision about protecting and promoting the unique legacy of a very special company, actively engaging with research and education in ways that influence the future of the discipline. For all these, typeface design owes Robin Nicholas a debt of gratitude.